MATTHEW GOING ON

Apprenticeships at Matthew Burt

Thirty-seven years ago, I found myself in a quandary. I had not used my Zoology degree to gain employment, embarking instead on a cabinet making apprenticeship with a national treasure called Richard Fyson who, along with his wife Ella, ran a workshop at Kencot in the Cotswolds.

I subsequently found myself, with my wife Celia, running our own workshop, where I had a serious intent to be both a designer and maker of furniture. I had only reached this point because of the confidence gained during my apprenticeship and the fact that Celia is a warrior. The quandary was simply the realisation that to succeed at the level of excellence we envisaged, we had to design, make, administer, market, sell and after-sell our furniture. Each discipline needed to be approached with the same level of acumen, creativity, drive, tenacity and compulsion as the bits we liked. A tall order.

We were also inspired by a need to support our local culture and economy. We returned to our delightful corner of Wiltshire where jobs were haemorrhaging out of agriculture. The overall situation had nose-dived in the 70s and was just emerging into the bright new world of the service economy; manufacturing was old hat, better achieved by others across the seas. Apprenticeships were seen as a tad passé but not in our world: our notion was essentially an 18th-century business model seeking a (then) 20th-century relevance. It became obvious that we needed to start building a team. We needed to take on an apprentice.

Derek came into our lives, bringing to us all the inherent responsibilities of becoming employers, the hurdle many artists, craftspeople and artisans are fearful to jump. What an initiation into the grown-up world. Why so difficult? Surely one of the best actions any of us can undertake is to provide a meaningful, dignified job for someone. Was there any help to do so? Precious little. Apprenticeship schemes were very thin on the ground. The government, to give it its due, did introduce the TOPS scheme, which was aimed at those entering the building trade and was surprisingly successful, launching many into the practical world of doing. Education made a power grab to fill the void left by industry’s, and others’, abandonment of apprenticeships. This was well-intentioned but training is rarely safe within the constraints of education. I feel that one becomes educated in order to become a civilized citizen capable of contributing towards society’s collective intent. One is trained for a job or task. It is a bridge too far for educationalist to take on the minutiae of training, although it is self-evident that one cannot receive specific training unless one has been adequately educated.

Derek was a great success, the first of twenty-five that have subsequently made their way through our workshop. With none have we found an official scheme that was practical, unintrusive, not requiring us to fulfil the government’s vision of what a furniture maker should be, often so wide of the mark and obviously imposed by theoretical, target driven agendas, devised by well-intentioned theoreticians. This is a pity. What happened to the flexibility of the day release or block release of the old technical colleges, whose courses were often tailored to local industry’s needs? I know it is difficult for the collective to trust the individual and that it has become increasingly so since the onset of the digital world’s capability to over-manage and record, especially as all must now be supported by ‘empirical evidence’. The unintentional withdrawal of trust, that was so manifest in the old technical colleges’ relationships with local employers, has had profound, unexpected effects. Who knows best how to impart specific skills?

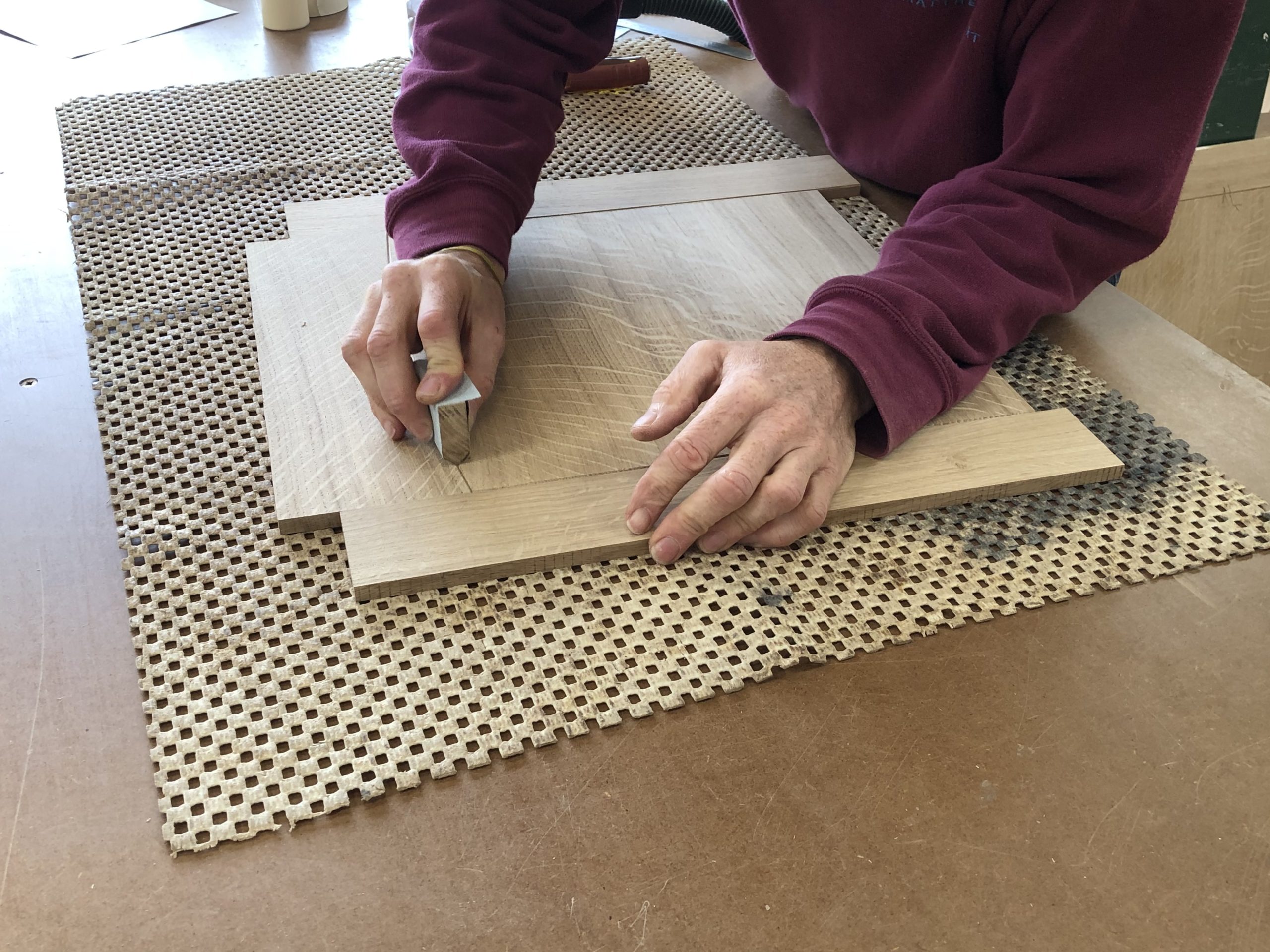

Our decision was to create our own scheme, essentially based on the time-tested principals of mentoring alongside consummate craftspeople, one-to-one demonstration, of giving responsibilities and not berating if they cock-up or fail. We have all been through the same process. No one wants to get it wrong and even here in my design studio, twenty yards from my workshop, I can feel the energetic wave of horror when a maker makes a mistake. No words of retribution are required, they have suffered enough. Just put it through the bandsaw and start again.

This journey is a brave undertaking, there is no piece of paper at the end of it, no certificate, no recognised qualification, just you have undertaken an apprenticeship with Matthew Burt. Arrogant, maybe, but all who have chosen to work within the industry are still doing so. They and we both are risk-taking to embark upon that journey.

I would like to dispel the modern supposition that we offer apprenticeships as an educative service, we do not. We do so in order to keep alive the skills and attributes necessary for us to continue to design and make furniture, to perpetuate and enhance the skills within our business. We use an 18th-century approach as we seek (now) a 21st-century relevance. The risk is worthwhile, the gift they receive after those six years enables them to manifest theirs or others’ ideas, that is very powerful.

Our apprenticeship scheme is a five-year programme with an extra year contracted in. That is the classic 10,000 hours, as identified by sociological research, as the time necessary to become very accomplished at something, being it playing a musical instrument, delivering babies or playing fly-half for your country. It is similar to the time any professional may be expected to train, the equivalent of a second degree. Our aim is to get the apprentice beyond the merely analytical into, arguably, the more profound and deeper intelligence of the intuitive or perhaps muscle memory. Nobody can argue that a peregrine in full stoop is not a form of mastery, capability and intelligence. To return to the sporting analogy, a fly half who receives the ball and reacts, may break through; the one that does so, but thinks, is normally stopped. We aim to take them to the space where they react.

We only offer apprenticeships after careful vetting and scrutiny. I am trying to give them the gift of ‘being’ a maker. The truth is that as education is the precursor to training, so the analytical grunt comes before the sun-lit uplands of trusting intuition. We know that some are born to be excellent at given tasks, however, we are also reassured that you are not necessarily a victim God or your genes. Neurophysiological research has shown that you can alter the neural pathways in your brain through application and practice. That is hugely life-affirming. You can alter who you are through application, diligence and the opportunity to do so. This is what we set out to do in our apprenticeships. The magic of seeing a young person become a capable, consummate practitioner has always been the reward for both education and instruction. I remember an apprentice who was three years in, staying on late to make a gift for their mother’s birthday, always a good sign that they are on their way. He was making a tray or something similar. He came to me in conversation “I don’t think there’s anything I couldn’t make in wood if I wanted to”. “That’s my boy, go get in there”. I did not disillusion him because I knew what he was feeling. He was, indeed, on his way towards the confidence of ‘being’ a maker.

Our dedication to our approach to apprenticeships has paid off. We are now an eight-maker business designing and making what we see as beautiful English furniture, from English timber and which speaks of our times. Each maker has been or is going through the six-year process. Some are twenty years plus into their making lives, others eight to ten years in and others just embarking on their journey. We are a business that has invested in skill. We have never taken money from any official apprenticeship scheme but we have gratefully accepted generous offers from clients wishing to support us. This has helped us create something that suits our intent. It has been a long, hard road, scattered with triumphs and a few disasters. We have purposefully concentrated on selecting people from our locality and those who have an emotional investment within it as we want them to stay with us. We are not an educational establishment with purely altruistic aims, we are trying to keep our practice relevant and alive. My wife and I have become firmly attached to this method of imparting skill and knowledge. At its best the apprentice will just have one-to-one tuition, but maybe five-to-one from those at the top of their game, offering advice and demonstration. Talk about an Oxbridge tutorial, the one-on-one time our apprentices experience far exceeds what universities offer, so much so that we now dedicate one, of the five mentors, per task to prevent too much advice and thus the causing of offence if one suggestion is followed in preference to another’s.

I was prompted into being a designer and maker of furniture through an incident at the end of my university life. I had finished my finals, been awarded my BSc (Hons) Zoology degree and was waiting for my next move. A fellow student invited me to view a gift he had made for his girlfriend. It was a small chest made in stained and polished plywood with a barrel-vaulted roof, opening on improvised leather hinges and decorated with dome-headed upholstery tacks. I looked on it amazed. “How did you do that”? “Well, I drew a plan first and I then I just made it”. I was transfixed, not by the object but by the process of manifesting an idea. I had taken exams every summer from the age of 7 to 24 and I could no more speak that language than fly to the moon but, at that moment, I became determined to do so. I had managed to get an apprenticeship, during which I recognised what I saw to be a poignant contrast between the ‘book learning’ of my academic efforts, vividly juxtaposed with the hands-on, one-to-one copying and demonstration of my apprenticeship. I absorbed information and techniques at a speed and in a quantity which startled me. I recognised that this could not have happened without a combination of the two and I saw the value of both and the wonderful synergy that consequently blossomed. It is this that I try to give each of my apprentices.