WORDS ON WOOD

We buy our timber in the form of trees, whole trees that have been planked into various thicknesses. This allows us to carefully select and balance grain patterns when making your furniture. We painstakingly go so much further than randomly picking timber out of a vast pile with a ‘take it as it comes’ attitude. It is not enough that it is just wood, it must be sensitively selected and thoughtfully displayed for it to give of its best. Each tree will reveal its character, its past and its charms, each tree viewed tells that individual story. We also like to search out those maverick trees such as rippled ash, tiger oak, olive ash, pippy elm, quilted maple, lace wood: all these timbers have a more interesting tale to tell.

At the heart of what we do is wood. We aim to use it responsibly and we select it from managed sources, principally in the UK, with a little from Europe and the USA. With each tree we aim to expose its charms and memorialise it in pieces of worthwhile furniture.

A FEW MORE WORDS

At the 100% Design show in the mid-1990s there was a promotional evening around the theme of ‘recycled furniture’. Legions of visitors breezed past our stand muttering darkly that our furniture wasn’t recycled as they dashed towards stalls showing converted ladders, orange boxes or washing machines masquerading as furniture. Eventually I felt moved to respond to one unfortunate mutterer “but it is recycled; it is made from wood which is the ultimate recycled material, it’s just recycled sunshine and rain water, a gift of a material” and that is how I will always see timber.

A LOT MORE WOODS

There are precious few outlets for home grown timber and only a handful of sawmills left in our country that are still cutting local trees. We spend a lot of time seeking out these sawyers and searching for those British timbers that are grown and cropped in sustainably-managed woodlands. We are trying to find woods that tell the story of our nation: oaks, ash, elm, beech, walnut, sweet chestnut, yew, sycamore, maple, with occasional rarities such as holly, lacewood, boxwood, apple, pear and cherry.

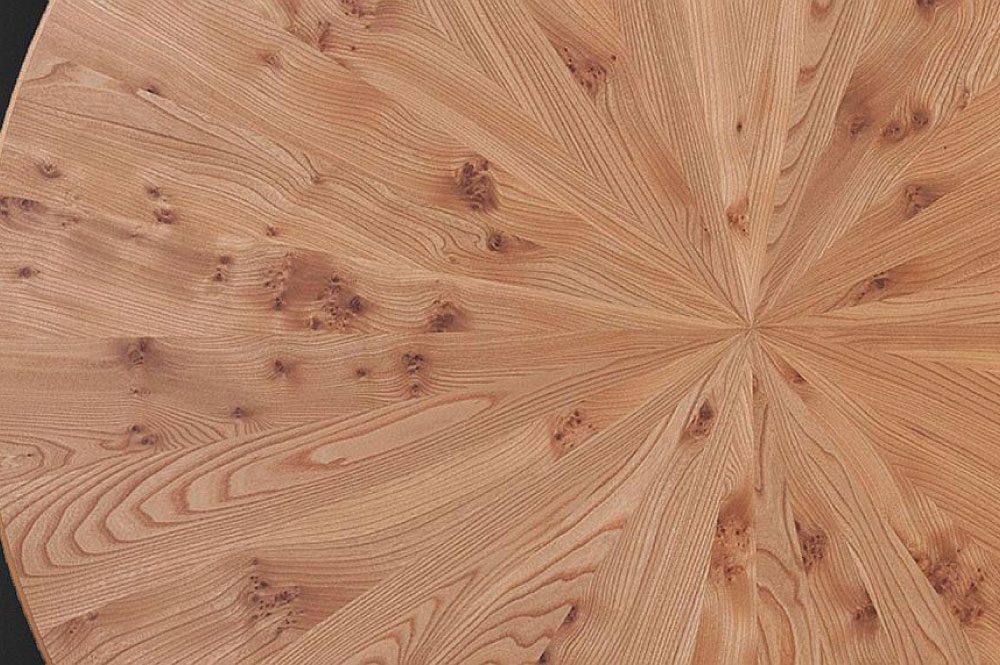

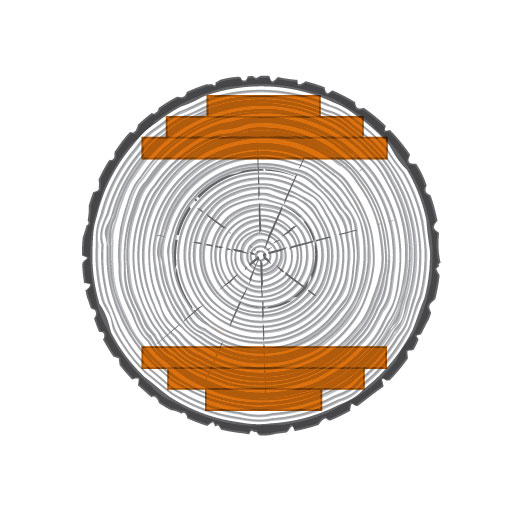

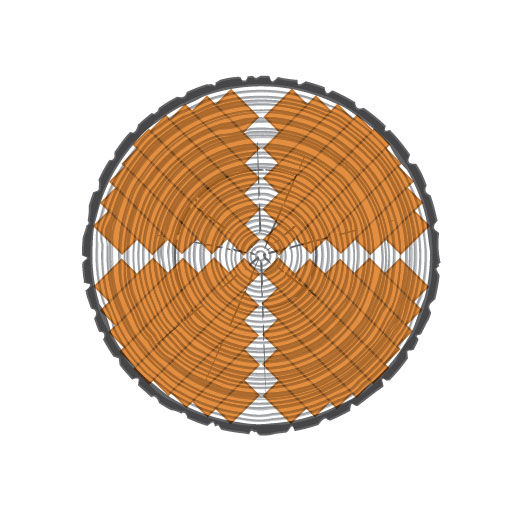

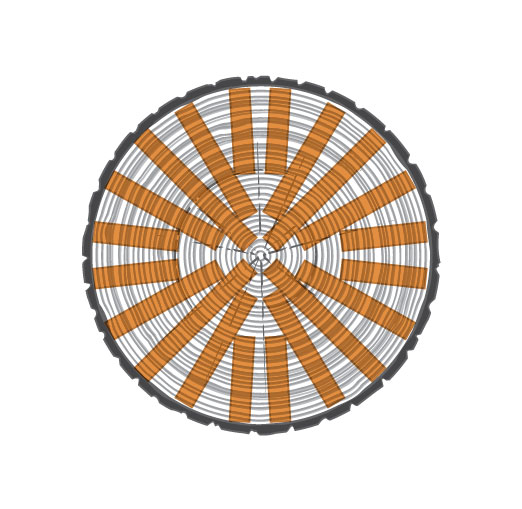

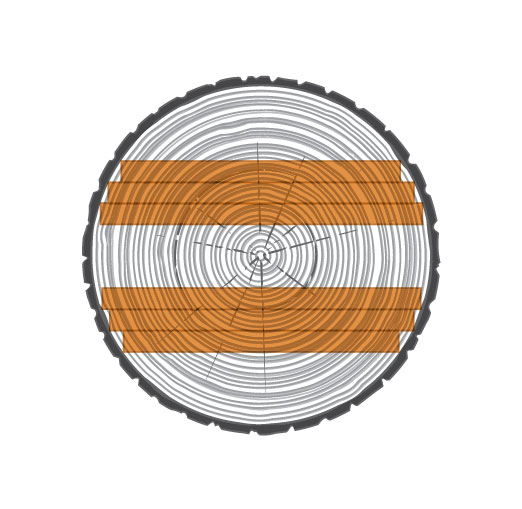

We principally look for three types of timber. Firstly, for stock, mainly one inch (25mm) and three quarter inch (18mm) thicknesses of oak and ash. We use these for carcase frames, back frames, drawer sides and bottoms, and we are looking for clean, straight-grained and the more stable cuts. The drawing in ‘woodcuts’ shows the basic cuts we use and which planks we select for which purpose.

Secondly, we are looking for 2 inch (52mm) and 1 ½ inch (38mm) thicknesses of similar timbers which we use for larger frames and carcase work, chair legs, table rails and legs.

Thirdly, and perhaps most interestingly, we search for the distinctive specimens within the British species; those that show their peculiar and individual history and have the scars to prove it. What follows are a few examples of what we are searching for.

OAKS

Hearts of oak, wooden walls of England, symbol of all things British; oak really is a robust, versatile and beautiful timber.

We use it in all its forms, often in frames, panels, and drawer sides.

We also search for aberrant individuals such as pippy, burr, tiger or bog oak.

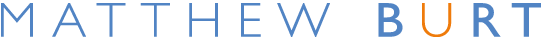

TIGER OAKS

There is a fungus called Fistulina hepatica (the beefsteak fungus) that occasionally colonises the roots of an oak, slowly causing a reaction with the tannins found within the wood. Tannins have been extracted from these trees, and particularly their bark, for centuries, to be used in the tanning/preserving of leather. This is one of the reasons the oak is so durable and renowned for being able to withstand the vagaries of the British climate, not to mention its suitability, historically, for making the wooden walls of England’s ships...

The reaction between the tannins and the beefsteak fungus starts with streaks of darker colour permeating the otherwise pale honey colour of the oak’s grain, it then progresses through a brindle oak stage until it becomes universally dark and it is then called brown oak. At each stage the timber merchants will wax it with words and increase their price. This is understandable because it transforms oak from beautiful to exceptionally beautiful.

BOG OAK

Around 6,000 years ago global warming was playing havoc with the seas around Britain. Huge tempests followed by deluges were felling oaks along the eastern side of the country. They lay buried in the silt reaching a kind of stasis in the anaerobic conditions of the bog. Twenty-first century farmers curse the plough-shuddering thump that indicates they have hit such a buried tree. But to the rescue comes a national living treasure from Kent, Hamish Low, who has mastered how to season such trees when they emerge. A very inexact science, fraught with failures and drama, sees some of these trees seasoned to be useable. The results can be delicious. The timber varies in colour from pitch-black at its exterior to an olive green at its centre. It is a remarkable timber, with a fascinating provenance, that we take great delight in converting into beautiful, useable memorials of these magnificent ancient trees.

BURR

This is another phenomenon that occasionally manifests itself in some British timbers. I like to search it out amongst elms and oak and, less often, find it amongst maple and sweet chestnut. I particularly search for it in elms because I’ve been trying to memorialise this magnificent tree’s timber since we lost the majority of them in the mid 1970s. Elm grain is an awkward, cussed timber that does not give up its charms easily. It is flecked with tool-blunting silica and it can ‘move’ mercurially in its seasoning, and, as anyone who has tried to split it with an axe will tell you, it is extremely tough. Once captured and honed, its rugged character is worn on its sleeve and its rich colour makes this the quintessential British timber.

RIPPLE

Another example of a maverick timber is that known as 'rippled'. In the case of ash, sycamore or maple, this phenomenon occurs occasionally and, in the case of oak and walnut, very rarely. It can be caused in one of two ways. Firstly, a mild version, which is caused by stress. An example of this would be a tree growing out of a south-facing bank, curving up towards the sun and developing a healthy ‘belly’ of growth on that side, leaving its impoverished back straining to keep it up and trying to prevent it from toppling forward. This might cause a mild stress ripple in the back of that tree.

Secondly, more dramatic rippling is caused by incorrectly-coded DNA in the gene responsible for producing the growth-promoting auxin (similar or equivalent to our hormones). The mutation causes the timber to grow in one direction as opposed to straight up towards the light. It’s as if the auxin recognises this and counters that the growth route should change, which it does, going in the opposite direction. This ding-dong, undulating, wave-like growth causes a rippling refraction of light when the timber is planked, planed and polished.

The Germans have cloned maple trees with this genetic ‘defect’ and have plantations of rippled maples growing for future use in the backs of violins. We Brits have a long way to go.

PIPPY

Elm often displays a characteristic speckling of small twig scars which, if intermittent and not too profuse across the timber, are known as pips, which are caused in an interesting way. The elm was brought to Britain by the Romans and introduced as a convenient, field boundary fodder crop. These 'crops' readily and speedily reproduced via root suckers, sprouting twiglets from their trunks which would be grazed by sheep, cattle and horses and, with each twig munched, a small scar would be left.

The next year another twig would sprout, often enduring the same fate, and over time this would cause knobbly protrusions to appear on the outside of the tree trunks. When cut through, planed and polished, mild knobbles show a small number of knots/pips, while the more severe and sometimes completely knobbly tree trunks show a mad cacophony of knots and convolutions. These are called burrs in Britain and burls in the USA.

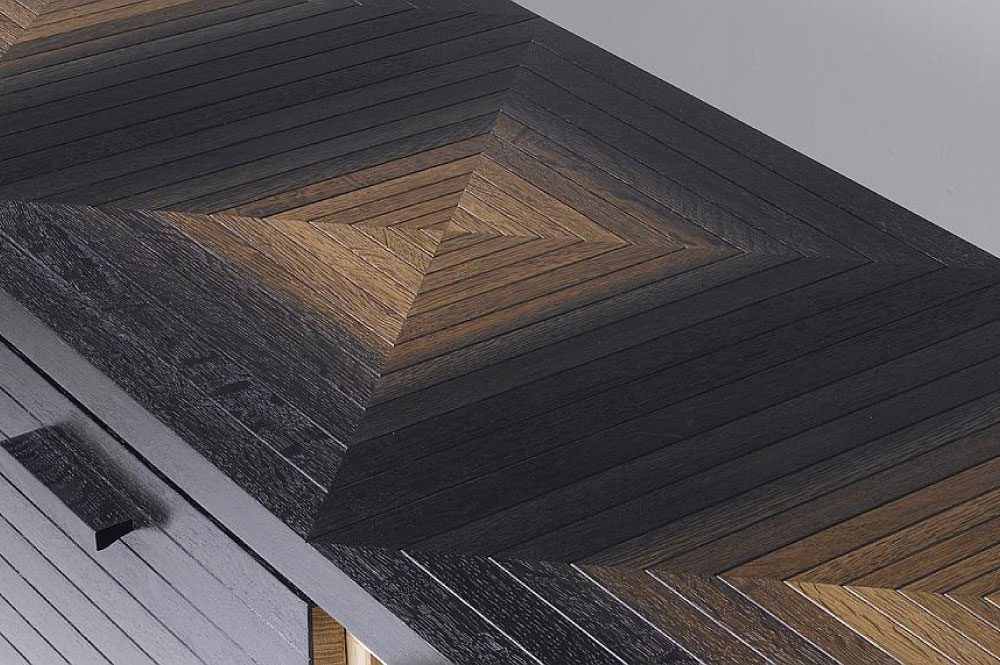

QUARTER SAWN TIMBER

If you look at the end of a felled tree, you will see the growth rings, known as annular rings for obvious reasons. They circle out from the tree’s centre depicting the number of years the tree has been growing. Radiating out from the centre but perpendicular to the growth rings in a star-like pattern of small, faintly visibly lines known as medullary rays. They are very faint in some species and more noticeable in others. They are like fragmented, undulating sheets of silk flowing vertically up the tree in their radiating pattern.

If a plank that has a surface running parallel to the medullary rays, such as the centre planks of the tree (see drawing in the wood cut section below) is planed and polished, these rays are clearly visible, prominently in oaks, spectacularly with London planes and subtly with sycamores and maples. Each species has its particular charm when displayed in this cut. The cut is known as quarter-sawn and is considered to be the most stable cut, it also adds to the grain appearance.

In the case of oak it is known as ‘silver’ grain and manifests itself as swirls and 'splodges' of paler colours running across the grain. It is much sought after; if you catch a glimpse of the panelling at the Palace of Westminster, you will see how dramatic it can be.

The quarter-sawn planks of the London plane are so dramatically different to the normally very bland timber that it has a different title and is another example of a timber merchant’s silver tongue; they call it lacewood and double the price.

END GRAIN

Looking into end-grain is like looking into time; the story of the tree's life with its good and bad years writ large within it. It is difficult to work with, but well worth the years of experimentation and research that enables us to sometimes incorporate it into our work.

An endlessly fascinating subject and for those that have got it bad there's dendrochronology, and if you’re feeling wild, forensic dendrochronology to dig a little deeper into.

CUTS

These are the growth rings laid down around very trunk, branch and twig of the tree. You can discern each year’s growth because of the sharp contrast between the large quick growth of the spring and the small slow growth of the late summer which result in the series of definable concentric rings.

The most recent growth and not fully lignified (rigidly woody) and offering a tempting entrée for woodworm, so best avoided. Also a paler colour and in some cases (yew, laburnum) a very different colour.

When looking at the end-grain they are seen as lines or flecks radiating away from the centre of the tree and are normally non-descript. When the timber is quarter sawn or rift cut, they are seen on the face quite dramatically in the case of English oak, spectacularly in the case of lace wood and discreetly with elm or beech.

The outer boards with swirls, classic woody look to them, almost like cartoon drawings of wood.

Usually straight grained with medullary rays very apparent in the grain. The most stable, in terms of movement, of the cuts.

This is a cut seldom used these days. It is by far the most stable cut, but as you can see it's very wasteful. We normally pick out the quarter sawn cut if we are seeking very stable material which we might use for drawer sides or components that fit and move between other pieces of timber.

Tending towards straight grained with little evidence of medullary ray flecks. Reasonably stable. It gives a clean unfussy look.