Here you’ll find our guide to the British hardwoods we use, from pippy oak tables to bog oak anniversary pieces, this guide covers natural features, grain patterns, and ideal uses. Explore the timbers below to see what makes each one unique, and how we bring their stories into the furniture we make.

Why We Choose British Hardwood?

We buy our timber in the form of trees, whole trees that have been planked into various thicknesses. This allows us to carefully select and balance grain patterns when making your furniture. We painstakingly go so much further than randomly picking timber out of a vast pile with a ‘take it as it comes’ attitude. It is not enough that it is just wood, it must be sensitively selected and thoughtfully displayed for it to give of its best. Each tree will reveal its character, its past and its charms, each tree viewed tells that individual story. We also like to search out those maverick trees such as rippled ash, tiger oak, olive ash, pippy elm, quilted maple, lace wood: all these timbers have a more interesting tale to tell.

At the heart of what we do is wood. We aim to use it responsibly and we select it from managed sources, principally in the UK, with a little from Europe and the USA. With each tree we aim to expose its charms and memorialise it in pieces of worthwhile furniture.

Responsible Sourcing

At the 100% Design show in the mid-1990s there was a promotional evening around the theme of ‘recycled furniture’. Legions of visitors breezed past our stand muttering darkly that our furniture wasn’t recycled as they dashed towards stalls showing converted ladders, orange boxes or washing machines masquerading as furniture. Eventually I felt moved to respond to one unfortunate mutterer “but it is recycled; it is made from wood which is the ultimate recycled material, it’s just recycled sunshine and rain water, a gift of a material” and that is how I will always see timber.

What We Look For in a Tree

There are precious few outlets for home grown timber and only a handful of sawmills left in our country that are still cutting local trees. We spend a lot of time seeking out these sawyers and searching for those British timbers that are grown and cropped in sustainably-managed woodlands. We are trying to find woods that tell the story of our nation: oaks, ash, elm, beech, walnut, sweet chestnut, yew, sycamore, maple, with occasional rarities such as holly, lacewood, boxwood, apple, pear and cherry.

We principally look for three types of timber:

1. Stock Timber

Oak and Ash, mainly in one inch (25mm) and three quarter inch (18mm) thicknesses. We use these for carcase frames, back frames, drawer sides and bottoms, and we are looking for clean, straight-grained and the more stable cuts. The drawing in ‘woodcuts’ shows the basic cuts we use and which planks we select for which purpose.

2. Frame Timber

Oak, Ash and occasionally Beech, in 2 inch (52mm) and 1 ½ inch (38mm) thicknesses for Chairs and Tables. We use this for chair legs, table rails, and heavier structures such as carcase work.

3. Distinctive Timbers

Scarred, Characterful, Historic. These are our most prized finds, maverick woods with story and identity. We search for the distinctive specimens within the British species; those that show their peculiar and individual history and have the scars to prove it. What follows are a few examples of what we are searching for.

OAK

Hearts of oak, wooden walls of England, and a symbol of British resilience - oak is a robust, versatile, and beautiful timber.

We use it extensively in our workshop, particularly for framing, panels, and drawer sides. Its fine grain and strength make it a favourite for both structural elements and statement pieces. From clean quarter-sawn cuts to richly toned brown oak, it adapts to many forms.

Take a look at our Aerofoil solid oak bench with armrest to see its timeless appeal in action.

While we often work with classic oak, we also seek out rarer variants like burr, tiger, bog, and pippy — each featured in more detail next.

TIGER OAK

Tiger oak is oak transformed by nature and time. A fungus called Fistulina hepatica, known as the beefsteak fungus, sometimes colonises the roots of a living oak tree, triggering a slow chemical reaction with its tannins.

This reaction produces dark streaks that ripple through the otherwise pale honey grain. As it progresses, the timber passes through brindle oak and eventually becomes brown oak, developing richer colour and dramatic figure at each stage. These markings are not flaws but natural features that reveal the tree’s unique history.

Timber merchants prize tiger oak for its rarity, beauty, and complexity. We choose it for pieces where a bold natural pattern adds depth and distinction to the design.

Explore our use of this exceptional timber in Roger’s Console Table and the Coopered Carver Chair, both fine examples of how a tree’s story becomes part of the finished piece.

BOG OAK

Around 6,000 years ago, the seas around Britain were in turmoil. Tempests and deluges brought down great oaks along the country’s eastern edge. Many were swallowed by the rising silt and lay preserved in the anaerobic stillness of the bog, a kind of time capsule.

To this day, farmers curse the jarring thud of a plough striking one of these buried giants. But from that frustration comes a rare opportunity. Thanks to master craftspeople like Hamish Low (a national treasure in his own right) some of these trees are now seasoned and salvaged for furniture making. It’s a process riddled with uncertainty, but the results can be sublime.

Bog oak varies in tone from pitch black at the outer edge to olive green at the core. Its density and age give it presence, gravitas, and a story deeper than any finish could mimic. This is ancient British timber, seasoned by nature, not by kiln.

We use bog oak sparingly and with reverence, for furniture that benefits from its rich depth and natural gravitas.

See how we’ve used this extraordinary material in our

Bog Oak Sideboard and our

Celebration Cabinet, each a monument to this rarest of woods.

BURR

This is one of nature’s most expressive flourishes — a timber grain gone wild. Burr occurs when a tree reacts to stress or injury by growing dense, contorted clusters of dormant buds. The result is a tangled, dramatic grain full of knots, whorls, and unpredictable beauty.

I search it out wherever I can: in elm and oak especially, and more rarely in maple and sweet chestnut. I’ve long sought burr elm in particular, trying to honour a timber that was once widespread and beloved, before Dutch Elm Disease claimed the majority of Britain’s trees in the 1970s.

Elm isn’t easy. It’s laced with silica that blunts blades, and it moves unpredictably as it seasons. It resists you, but once captured and honed, its rugged character is worn on its sleeve and its rich colour makes this the quintessential British timber.

We often use burr elm and burr oak where texture and complexity can take centre stage. See it in the grand form of our Five Pebbles in a Pool cabinet or in the more intimate, intricate surface of the Treasures Box, both pieces a monument to the tree’s resilience.

RIPPLE

Another example of a maverick timber is that known as rippled. In species like ash, sycamore, or maple, this striking visual effect appears occasionally. In oak and walnut, it’s vanishingly rare.

There are two known causes. The first is stress. Imagine a tree growing out of a south-facing bank, reaching towards the sun and developing a pronounced belly of growth on one side. Its shaded back, straining to keep the tree upright, creates internal tension. Over time, this can result in gentle rippling along the grain — a mild but beautiful distortion.

The second cause is genetic. A fault in the gene that regulates the growth hormone auxin can trigger the timber to grow off course. As the tree grows, the auxin seems to detect the error and sends the growth pattern back the other way. This to-and-fro produces an undulating, wave-like grain that catches the light in a distinctive, shimmering pattern once the wood is planked, planed, and polished.

Rippled timber is highly prized for its visual dynamism. The Germans, recognising this, have cloned maple trees with the mutation and cultivated plantations of rippled maple specifically for violin backs. We Brits have some way to go.

We use rippled timbers sparingly, often to elevate the interior of a piece, as seen in the Rocking Box, where rippled sycamore lends a hidden elegance.

PIPPY

Elm often displays a characteristic speckling of small twig scars. When these are spaced intermittently across the surface they’re known as pips, and their origin tells a curious story.

Elm was introduced to Britain by the Romans as a useful fodder crop for field boundaries. These trees spread quickly by root suckers, producing twiglets along their trunks. Grazing livestock would nibble them down, leaving behind tiny scars.

Each year the process repeated, twig after twig, nibble after nibble. Over time, this created knobbly outgrowths on the tree’s surface. When the timber is sawn, planed, and polished, the milder formations show up as attractive scatterings of knots, known as pippy. More extreme examples result in a dramatic, almost chaotic surface of convoluted grain, what we call burr in Britain, or burl in the USA.

Pippy timber brings movement, warmth, and visual rhythm to furniture surfaces. Its patterning makes it a favourite for statement pieces where natural ornamentation shines through. You can see it in action on pieces like our

Up and Over Five Drawer Chest or the

Whirly Gig Revolving Shelves.

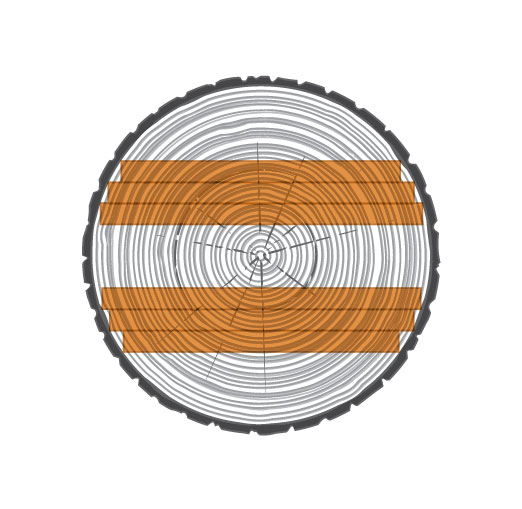

QUARTER SAWN TIMBER

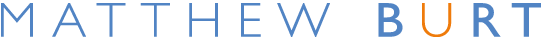

Look at the end of a felled tree and you’ll see its life written in rings. These concentric circles, the annular rings, chart each year of the tree’s growth. Radiating outward from the centre, perpendicular to those rings, are faint lines known as medullary rays. In some species they’re barely visible; in others, they shimmer like silk sheets rising through the trunk.

When timber is sawn so that the face of the plank runs parallel to these medullary rays (typically from the centre of the tree) the rays become strikingly visible once planed and polished. This is known as quarter-sawn timber. The result is not only visually captivating, but more stable and resistant to warping than flat-sawn boards.

Quarter-sawn oak reveals a distinctive feature called silver grain, swirls and streaks of pale contrast that ripple across the surface. It’s a cut we use frequently when grain definition matters, especially in statement cabinetry and architectural panelling. You can see its effect in historic interiors such as the Palace of Westminster, where the drama of the cut takes centre stage.

The same principle applies to London plane. Its quarter-sawn grain is so radically different from the standard cut that it even earns a different name: lacewood. And with that, of course, comes a heftier price tag — the timber trade’s poetic licence in action.

We used this striking material in our Oyster Box, a bold example of how medullary rays can elevate the most delicate of forms.

END GRAIN

Looking into end grain is like reading the story of a tree’s life. Each ring tells of a good year or a bad one, of seasons shaped by sun, rain, and time. It’s a cross-section of history, etched into timber.

End grain is notoriously difficult to work with. It blunts tools and demands precision, but we believe it’s worth the challenge. Years of experimentation have allowed us to occasionally incorporate it into our designs, adding striking contrast and narrative to the piece.

For those who love wood as much as we do, it’s a subject of endless fascination. If you’re especially curious, dendrochronology (or even forensic dendrochronology) might take you deeper still.

See our Low Stack Coffee Table for a striking example of end grain brought to life.

We’ve explored end grain in both structural and decorative ways, but few pieces show its charm quite like Cubed. This finely detailed set of drawers showcases the unique patterning and tactile appeal of end grain, and recently captured the public’s imagination — a video of it went viral with over 11 million views.

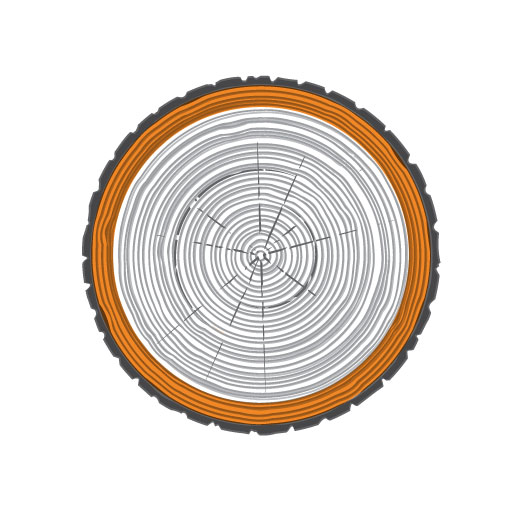

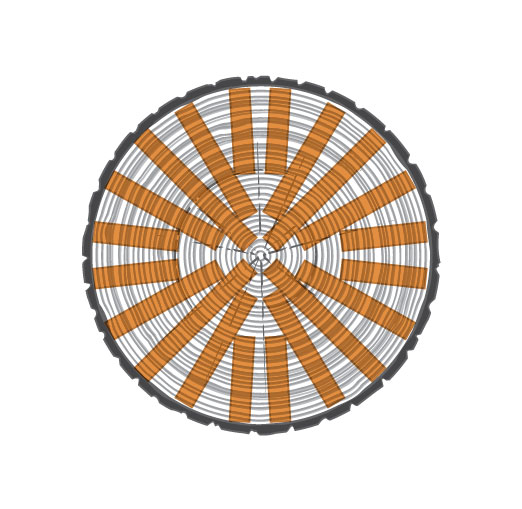

CUTS

These are the growth rings laid down around very trunk, branch and twig of the tree. You can discern each year’s growth because of the sharp contrast between the large quick growth of the spring and the small slow growth of the late summer which result in the series of definable concentric rings.

The most recent growth and not fully lignified (rigidly woody) and offering a tempting entrée for woodworm, so best avoided. Also a paler colour and in some cases (yew, laburnum) a very different colour.

When looking at the end-grain they are seen as lines or flecks radiating away from the centre of the tree and are normally non-descript. When the timber is quarter sawn or rift cut, they are seen on the face quite dramatically in the case of English oak, spectacularly in the case of lace wood and discreetly with elm or beech.

The outer boards with swirls, classic woody look to them, almost like cartoon drawings of wood.

Usually straight grained with medullary rays very apparent in the grain. The most stable, in terms of movement, of the cuts.

This is a cut seldom used these days. It is by far the most stable cut, but as you can see it's very wasteful. We normally pick out the quarter sawn cut if we are seeking very stable material which we might use for drawer sides or components that fit and move between other pieces of timber.

Tending towards straight grained with little evidence of medullary ray flecks. Reasonably stable. It gives a clean unfussy look.